from Syngress Press, The Mezonic Agenda, Chapter 18: Seattle,

Washington

Chad Davis’s Home

Chad was not

a morning person. He worked best after the sun had set. If he wasn’t teaching,

he would set his alarm clock for noon

and occasionally followed lunch with a mid-afternoon nap. His internal clock

was on hacker time. Even though Davis was not a hacker, he found

that both his work and his associates were more approachable at 2 A.M. instead

of 9 A.M. Even though he had been on an airplane for half the previous day, Davis

could not go to sleep without tinkering with something. Usually it was some new

debugger, plowing through e-mail, or reviewing papers, but last night he had

more pressing concerns: What the hell did Baff have on that CD? It must have lingered in

his sleep, because he was up before nine o’clock preparing a meal he was very

unfamiliar with: breakfast. As the eggs scrambled and bread toasted he powered

up his laptop ready to attack the CD again. Setting his plate down with eggs, toast,

some microwaved bacon, and condiments, he remembered

to call Hans

Sheridan, one of his best friends,

and an FBI agent.

“Good morning,” Davis proudly said

as Hans picked up, making sure to point

out his accomplishment.

“Chad? Are you sleepwalking or something?

It’s not April Fools is it?” Hans

replied with characteristic sarcasm.

“I know, I know. Hey, there’s a first time for everything. Haven’t heard from you in a while. How are things going?”

“Pretty good.We’ve been busy this past month. I had a couple

of trips outside of the field office these past few weeks and now I am back home. How about you? What do I owe this relatively

early call to?” “Well obviously I would not be calling you before noon on a Saturday if I didn’t have

a favor to ask.”

Hans laughed,

“As usual.What is it? A parking

ticket? Indecent exposure? Hey, you just came

from Amsterdam,

right? I have some penicillin if you need it.”

Chad

hesitated for a minute. He quickly thought about what he was about to ask and

where he was about to do it from.

“Real funny. Hey Hans let me call you right back. I got breakfast on the

stove.”

“Wow, not only are you up in

time for breakfast, you’re actually cooking something! This must be serious.

Ok, don’t keep me waiting too long.”

“Just give me a minute,” replied Davis and hung up. He walked over

to his desk, quickly grabbing a bite of his now lukewarm eggs and toast. Among

the piles of papers he grabbed his cell phone and called Hans

again.

“Sorry about that. My eggs were browning.”

Hans smirked,

realizing by his caller ID that Chad

switched from his land line to his cell phone.“No problem. I hope they still taste good.” “Yeah,

as good as I’ll ever make them. So, I have a question for you. I was at the

airport in Amsterdam

and got questioned by Interpol…” Hans

interrupted inquisitively, “Interpol? In Amsterdam? What were they doing

there?”

“Yeah, well, hindsight is always 20/20. I guess your bureau-trained paranoia

hasn’t rubbed off on me. So can you find out any info on the agent that stopped

me?”

“I can try.You got his name?” asked Hans.

“Sure, hold on a second.”

Davis grabbed

his carry-on bag and searched through his papers, pens, and accumulating

garbage. He grabbed a card with his scribbled writing and reached for his cell

phone, “You still there? Ok, it’s Jonas Borgstand.

B-o-r-g-s-t-a-n-d.”

“Got it. Give me an hour or so and

I’ll see what I can get. Maybe you should get some sleep.”

“Thanks, I owe you one.”

Ending the call, Davis’s

stomach growled at him for ignoring his now cold, and

probably tasteless eggs. He sat down and stared at them on his plate,

contemplating what else he was going to eat. Cereal is

always a good start to the day.

After a couple of bowls he decided to plunge into that CD and not come

out until he figured out what Baff wanted to show

him. Davis

opened his laptop, ready to do battle. Some sleep was all he needed to get a

fresh perspective on Baff ’s little brainteaser. Davis knew that

potentially he could spend weeks trying to decipher Baff ’s cryptic text file. Maybe

it doesn’t mean anything, knowing Baff he probably

just needed to take a note or something and accidentally saved it to disk.

Davis didn’t

believe that, but it was too early in the morning to admit he had intellectual

limitations and just couldn’t figure it out. It was partially an excuse to try

some of his honed reverse engineering skills. Reverse engineering software is

the art and science of understanding and manipulating software after it has

been compiled, and during the past three years Davis had become a

master. When a person writes a computer program, they tell the computer’s

hardware what to do by giving it a series of instructions. At their lowest

level, computer instructions are represented as bits—binary digits that have

two states, on or off, one or zero. Most of the time, when one sees these

instructions, they are represented in hexadecimal (base 16). Instructions are

usually visible if one opens an executable file in a hexadecimal editor. An

executable file is just a collection of these instructions and some data that

these instructions will operate with or on.

In the early days of computing, programmers would write complex programs

using these instructions directly. Programmers who wrote endless strings of

hexadecimal numbers would command absolute power over machines that occupied

rooms the size of warehouses. Efforts were made to make the process of writing

machine instruction easier by allowing programmers to write short, English-like

codes to represent a series of numeric instructions.These

mnemonics became known as assembly language. When a programmer was finished

writing his or her instructions in assembly, a piece of software known as an

assembler would convert these mnemonics into their machine-instruction

equivalents. People soon realized that they were writing the same sets of

instructions over and over again. A mechanism was needed to both encapsulate

these instructions and to make the process of controlling a machine simpler.

The result was the development of so-called high-level languages that allowed

users to program with English-like constructs.These

program files would then be converted into machine code using a compiler. Most modern

applications are written by teams of programmers using various high-level

languages like C, C++, and Java.

Davis realized

that a huge misconception about compilers lingered in the minds of programmers.

Most programmers believe that once an application was compiled and in

machine-executable form that it was unalterable. Beyond that, many believed

that any secrets hidden within the lines of source code like passwords were locked

in an impenetrable vault by the compiler, a vault to which no one had the

combination.

Reality, he knew, was quite different. People like Baff

made their livings by changing the behavior of software. Most of the time, the

behavior that they worked to change had to do with the software’s restrictions

on copying or distributing it. Many companies for example, choose to make users

“activate” their products either through the Internet or by a key given over

the phone. This activated software would then be fully functional on the

machine it was originally installed on but useless on any other machine. Other

software vendors had begun to raise the ante by distributing hardware “keys”

that needed to be inserted into the machine to run their application. All these

methods were created in an effort to stop software pirates from copying and

distributing software without paying for it; over the years all had been

broken.

Davis’s

interest today was not in removing copy protection; it was getting that damn decryptor to work. His first step was to use a hex editor to

examine the decryption program.

Abstractly, there are two ways to manipulate and inspect software:

statically or dynamically. Dynamic analysis is done while the application is running,

usually by watching the application execute instruction by instruction with a

debugger. Baff obviously had thought hard about

protecting against this. On the plane Davis hit a silicone wall. He threw

several commercial debuggers at the application, even an advanced one that Davis himself had written—all failed. Baff

was good.

It was now time to do some static analysis; dissecting the binary file itself

using some inspection tools. Davis’s first step was always a hex

editor.

To the casual user, the output of a hex editor is a sea of garbage; meaningless

characters that somehow must miraculously come together to make a program do

what it does when they execute it.

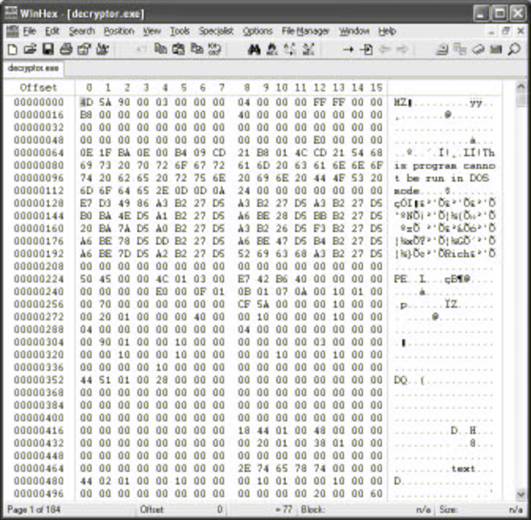

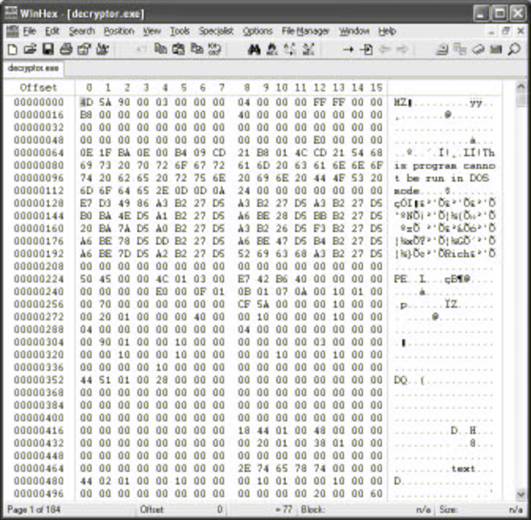

Output of the Hex Editor

Davis looked

at the output and saw much more. He saw an application, baring its secrets, its

purpose. He had learned to do some amazing things by editing a program directly

in a hex editor over the last few years. He could change how the application

behaved, how it responded to input and how it looked. He could also add

features and change flawed ones at the lowest possible level.

This skill had made Davis a lot of money in 1999, when

many companies were throwing money at anyone who could soothe their Y2K computer

fears. Most companies were still running ancient software that used two digits

to represent which year a transaction or event was taking place.

When the original programmers had developed these applications no one thought

that they would still be in use a decade or sometimes two decades later.The fear was that when the year rolled around from 99

to 00 many applications would fail possibly by instantly archiving transactions

that took place in 2000 as 100 years old, automatically voiding transactions,

dividing by the year 00, or other unimaginable horrors. It was during this

period that Davis

mastered the art of bending software to his will. He would have to modify old

applications for which the source code was either lost or unavailable, and make

them work with the new date format. If anyone could make this decryptor give up its secrets, it was Chad Davis. Davis

skimmed the output from the hex editor. Nothing immediately obvious.There

were some strings that looked like ASCII art. A few

interesting phrases: “Success…the key is

yours!" followed by a peculiar 32-character long number. By its length and its placement

within the binary Davis

assumed it could be only one thing: a password hash!

51d2b210d1ad862d781f065eb22d9370

Interesting Phrases and Numbers

Hashes were a testimony to modern cryptography. Davis had used their

power several times in his programming days as a graduate student. A hash

function reads a long string or file as input and produces a “digest” of that

data. Ideally, the security properties of these functions ensure that the

digest looks random and does not leak any information about the data itself,

and that other messages cannot be found that produce the same digest.

Specifically, what makes these numbers interesting is that they have a few very

desirable properties.

First, finding an input that produces a given hash is (hopefully) extremely

hard. Second, finding two inputs that hash to the same result is difficult (if

not impossible).Third, knowing the hash, you cannot recompute

the original data; thus, hash functions are also known as one-way functions.

Finally, small changes in the data can cause drastic changes in the value of

the computed hash.

One application of hashes is to ensure that files are not tampered with.

One can compute the value of a file when it is in a known,“good” state and save that hash value in a safe

place. Later, one could compute the hash of that file again and compare the old

value with the new: if the two match, the file has not been tampered with. It

was doubtful that this was the way Baff was using it.

For one, it was stored in the file itself.That means

if the user changed the file, or a part of the file, they could also recompute and change the stored hash value. Baff was too clever for that. Another popular use of hashes

was to store passwords. Davis

figured that this is exactly what Baff was doing.

Baff,

you bastard! The general problem with storing passwords in a

program is that an attacker with a hex editor might be able to see that

password stored in binary and then use it. Using hashes was a good alternative.

Davis

knew that this is how most of the widely used operating systems like most

flavors of Linux, UNIX, and Windows managed passwords. In most versions of

Windows, for instance, when a user logs in, a hash of the password is calculated

and then compared with a hash of the original password stored when it was

initially set.The result is that nobody’s password is

actually stored on the machine, only the hashes.This

is the reason that a system administrator is often unable to tell you your

forgotten password, but they are able to set a new one. Apparently Baff had taken the same approach with his decryptor.

Like any cryptography though, this could be broken.The

only question was how long would it take. Davis had used some of the dubbed “password

recovery” tools—which usually were used as “password theft” tools—like L0pht

Crack for Windows passwords and John

the Ripper for UNIX/Linux. For a funded project through the U.S. Navy Davis had

also written several of his own tools. Most of these tools worked by “bruteforcing” passwords—trying various combinations of

letters, numbers, and special characters, computing their hashes, and then

comparing these computed hashes with the one stored. For operating system

passwords, many tools can recover a reasonably complex password from a hash in

a few hours, likely trying several million combinations in the process. Davis

knew that his task was harder. For operating system passwords, there are a few

things that make the process easier. For one, usually there is a known maximum

length like 8 or 16 characters. Davis had no idea what kind of password

Baff was expecting. One character,

ten, a hundred; all possibilities.

Davis did not

have that luxury. His testimony was a couple of days away, and he had to know

what Baff had found.

When Davis

studied cryptography as a graduate student at Carnegie Mellon he was amazed at

how widely these techniques had been used during the two World Wars. Many

battles had been won or lost based on how skilled each side was at breaking

encoded messages. What amazed Davis at the time was how breakable

many of the systems were.The important thing was how

long it would take to break it.

Ok Baff, let’s do

this…

Davis knew

that the sledge hammer approach would not work in time. There had to be another

way. There were two widely used families of hashing algorithms: the Secure Hash

Algorithms (SHA) and the Message Digest (MD). Baff ’s hash had 32

hexadecimal characters, which meant it was probably either MD4 or MD5, both of

which had a 128bit = 32 hex character hash value. Most of the world had moved

from MD4 to MD5, which was more difficult to crack. From what he had seen so far,

Davis

was pretty sure that Baff would pick the harder one.

MD5 it is.

Again, trying to attack the cryptography directly was not an option. Davis

recalled the first try-and-buy software that he cracked. He changed the

hard-coded date that helped the software compute its expiry time. In the early

days some software developers started to use this method to get around the

“setting the system clock back” trick. Looking back, Davis recalled

what a horrible scheme that was. He changed the stored date from 1993 to 2013

and the application worked like a charm. Fifteen bucks saved!

He was about to apply the same principal here.

If I can calculate the hash to a password

that I do know, maybe I can replace the stored key with the fake key.Then I enter the password that corresponds to that key!

Damn I’m good!

He was good, but so was Baff.Obviously Baff wanted him to crack this thing

if anything happened, but why did he have to make it so goddamned difficult? Davis

opened a web browser and found a free MD5 hash calculator.

Hmmm…now for a password…ah, why not… Davis entered

the string “advice” and the resulting hash was: fd99cadea9d8ef6a1ffcc52a2e3e8017

Davis had a

plan. He had his string. He had its hash. It was time for this application to

suffer. Davis

again opened up his hex editor and faithfully replaced the original hash with

the new value he computed and saved the modified file as c:\cracked.exe.

Success!

Now, the moment of truth…

Davis ran the

modified file and once again was asked for the key.This

time things were different, this time he had made his own key. Davis

typed “advice,” his newly contrived password.With a

quick press of the Enter key, success!

He looked with amazement at the screen in front of him; he had done it.

He gave the application the location for Baff ’s mysterious encrypted file and gave it the location to

save the decrypted file. Within seconds it had produced its result. Davis

quickly opened the decrypted file in his hex editor. He didn’t recognize the

symbols, characters, and patterns before him. He spent the next several minutes

scrolling through it. It wasn’t an executable, it

didn’t have the right headers. It was not a document file,

at least it was not in any format that he had ever seen before. He slammed his hands

down on the desk.

This is complete garbage. Son of a bitch! I

don’t have time for this! A ringing phone interrupted the audible

string of profanities now freely flowing from him.

“Hello!”

“Hey; easy. What the hell is the matter with you?”

“Sorry Hans. I am about to take

an axe to this CD I’m working on cracking.”

“CD? What are you joining the

Spice Boys or something? You may not wanna do that

just yet. On a more pressing matter that boy of yours, Jonas

whatever-the-fuck-his-name-was, is a ghost; Interpol never heard of him.”

A cold shiver ran down both of Davis’s arms. He was afraid of

this, but what did it mean?

“Chad, you still there?”

“Yes, I’m here. Can we meet somewhere? How about Redmond Town

Center,Thai restaurant in 20?”

Davis’s voice

was overtly shaky. He had dealt with criminal elements before but they were

hackers, guys who harmed bits, not people.

Had Jonas

killed Baff? Is he trying to kill me?

The thought was too much for him to bear.

“I’ve got a better idea.” Hans said

in a decidedly different tone.

“Remember that place where we met up about a month ago, I’ll meet you

there in an hour. Ok?”

“Ok. One hour.”

Davis hung up

the phone. His left hand trembled slightly as it let go of the receiver. Hans’s last words had really shaken him: The

place we met last month? Why didn’t he just say Starbucks on 45th?

Is my phone being tapped? Does Hans know something

he’s not telling me?

The only explanation for Hans’s

vagueness that Davis

could imagine was that he suspected a wire tap. It was now more important than

ever to find out what Baff was trying to tell him.

Davis turned

his attention back to the CD and tried to put the failure of the last two

hours’ efforts behind him. His next step was to use a disassembler

to try and find out why he had failed and how he could unlock what Baff had spent so much effort to keep hidden. A disassembler was the opposite of an assembler.Whereas

an assembler converts assembly commands into machine instructions, a disassembler attempts to convert machine instructions into

assembly instructions that are more easily read by humans rather than machines.

Almost every operating system ships with an assembler and a disassembler

that are installed by default. As Davis found out early in his

professional career though, understanding how a binary works was an art, one

that could not be fully captured in a rudimentary disassembly tool. Sometimes

the process would take days of staring at complex control flow graphs and

looking at hundreds of pages of assembly code.To be

successful one had to become a detective, following digital clues and making

leaps of deductive reasoning.

The right tools were essential. Davis opened the decryption program

in Datarescue’s Interactive Diasassembler

(IDA Pro). IDA

was not a tool for the casual computer user; it was a craftsman’s tool, a tool

meant to be wielded by software assassins.

Within 25 minutes of staring at IDA Pro Davis realized why his approach

was doomed to fail. It appeared as if Baff actually

used the characters in the unknown password itself to encrypt the file.The original password was needed if he was to make any

sense of the encrypted file in time.

Davis looked

down at the clock in the bottom right-hand corner of his computer screen, and

began to shut down his laptop and place it in a small carrying case.

I hope Hans

has some answers! A few dozen feet away in a grey van two men

stared intently at the black and white video feed from Davis’s home.

Since listening in on the conversation between Davis

and Hans minutes before, they knew one

of them had to call Danko. People who knew his

identity tended not to live very long; he made sure of it.

“So are you gonna call him?”

“I wouldn’t call that man if his

sister was the last woman in the world!” replied the first man.

Even with rap sheets neither man wanted to call Danko

with the news that Davis and Hans

were on to him. After a minute one finally caved in.

“All right, give me the damn phone. Someone’s in a load of trouble.”